Imagine you are the prime minister of a developing country. You have been working hard for many years to reform your country's economy so that growth rates can be improved and sustained, and poverty reduced. Just when you were confident things were on the right track and that clear progress was being made toward meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), out of the blue, some World Bank poverty experts come up with new calculations revealing that the updated international poverty rate in your country is much higher than previously thought. Surprised, you gather your thoughts and request that your own experts carefully review their statistics. Yet they, too, review the empirical evidence and confirm that poverty is more pervasive than you thought.

That is more or less the situation in which many policymakers in developing countries find themselves since the release of the World Bank's internationally comparable poverty estimates. The news was sobering indeed: a study by my colleagues Martin Ravallion and Shaohua Chen, which adjusts the yardstick for measuring global poverty to $1.25 a day in 2005 prices, reveals that more people are living in poverty in developing countries than previously thought, based on the World Bank's prior international poverty line of $1.08 a day in 1993 prices. After a major revision of the method used to calculate poverty, they estimate that 1.4 billion people, or 25 percent of the population of the developing world, live below the international poverty line. Previous work published in 2007 had estimated that 950 million people, or 17 percent of the developing world's population, were living on $1.08 a day or less. By the updated measure, an additional 400 million people are living in poverty.

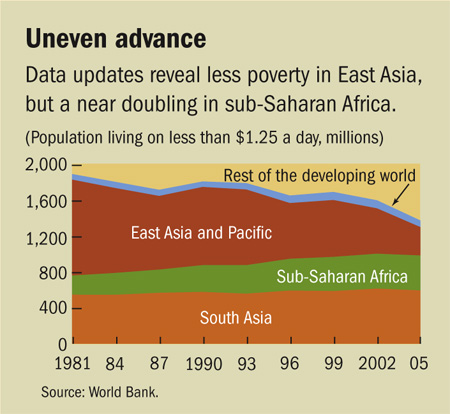

The new study also found poverty falling from 52 percent of the developing world's population in 1981 to 42 percent in 1990 to 25 percent in 2005, with a constant rate of decline for 1981–2005 of about 1 percentage point a year for the developing world as a whole. It concluded that the world is still on track to reach the first MDG of halving the 1990 level of poverty by 2015.

Dramatic shift

The main reason behind such a dramatic shift in numbers is straightforward: the World Bank has recalculated the number of people living in extreme poverty using recently released results from the International Comparison Program and 675 household surveys covering 116 countries from 1981 to 2005. The old "dollar-a-day" poverty line was chosen to represent the threshold of extreme poverty. It was based on the (then) best available cost-of-living data from 1993, but it has been found that these data underestimated the cost of living in many poor countries. Because the cost of living in poor countries is now known to be higher than was thought, the number of people shown to be living in poverty is also higher.

Although the level of poverty across all developing countries is higher than previously estimated, poverty has actually fallen over time. The general methods used to establish the international poverty line and to measure poverty rates have been consistent since the first estimates were made almost three decades ago. What has changed is the reliability, timeliness, and comprehensiveness of the data.

The updates reveal big successes in poverty reduction, particularly in East Asia (see chart). Looking back to the early 1980s, it had the highest incidence of poverty in the world, with almost 80 percent of the population living below $1.25 a day in 1981. By 2005 this had fallen to 17 percent. There are about 600 million fewer people living in poverty by this standard in China alone, though progress there has been uneven over time.

Yet progress is not limited to East Asia—there are many examples of falling poverty rates. In the developing world outside China, the $1.25 poverty rate has fallen from 40 percent to 29 percent over 1981–2005, though not by enough to bring down the total number of poor, which has stayed at about 1.2 billion. India has made notable strides, reducing poverty from almost 60 percent in 1981 to 42 percent in 2005, based on the international $1.25-a-day line. The rest of South Asia has made similar progress. After many years of stagnation, poverty in Latin America has begun to fall, from 11 percent in 2002 to 8 percent in 2005.

Rethink and adjust

But advances are uneven, and the level of poverty in parts of the world remains unacceptably high. In sub-Saharan Africa, the $1.25-a-day rate was 51 percent in 2005—roughly the same as in 1981. Given the depth of Africa's poverty, even higher growth will be needed than for other regions to have the same impact.

Despite the sobering news the numbers convey, the updated estimates may help the international community and policy-makers in developing countries rethink and adjust their development strategies and policies. Empirical work by World Bank researchers over 20 years has shown that the incidence of poverty tends to fall with sustained economic growth. Using three successive household surveys from a sample of about 80 countries spanning 1980–2000 and the dollar-a-day poverty rate, Ravallion (2007) estimated that the growth elasticity of poverty reduction is negative—that is, their trends tend to match—in about 80 percent of all cases, though poverty tends to be less responsive to growth in high-inequality countries. His findings are corroborated by the new global poverty numbers. Regional growth rates and changes in the percentage of people living below the international poverty line over the past quarter century tell the same story: East Asia recorded the highest average growth rate during 1981–2005 and also the largest decline in poverty. By contrast, sub-Saharan Africa and the Europe and Central Asia region had the lowest growth rates and performed the worst in their poverty reduction efforts.

The key policy question, therefore, is how sustained growth is generated to reduce poverty. Evidence shows that high rates of growth are associated with openness. Greater trade openness does not always promote growth, and it can also have distributional effects that dull the impact on poverty. But, as a rule, trade openness comes with higher growth and the poor tend to benefit.

Key to competitiveness

The correlations between growth, improvement in trade indicators, and poverty reduction may result from the fact that openness promotes economic strategies based on comparative advantage, which is the key to a country's competitiveness. Michael Porter (1990) famously identified four sources of a nation's competitive advantage:

• sectors or industries making good use of factors that are abundant domestically,

• large domestic markets that enable firms to reach scale,

• industrial clusters, and

• vibrant domestic competition that encourages efficiency and productivity growth.

For any country, the domestic abundance factor actually refers to comparative advantage as reflected in its endowment structure. The industrial clusters and domestic competition factors depend on whether a country adopts a development strategy that is consistent with its comparative advantages. This is because a country whose industrial development defies its comparative advantage will end up with a closed domestic economy and a noncompetitive market, because domestic firms will not be viable in open, competitive markets, and will have to rely on subsidies and protection for survival (Lin, 2007).

Industrial clusters would also be hard to build and sustain in such situations, because the government would not be able to subsidize and protect a large number of firms in a single industry at the same time, allowing the formation of a cluster. When a country follows its comparative advantage, the large domestic markets factor becomes unnecessary because industries are able to compete in global markets.

Exploit comparative advantage

Porter's four factors therefore boil down to a single prescription: allow each country to exploit its comparative advantage. Any low-income, capital-scarce country attempting to develop capital-intensive industries against its comparative advantage will end up with a closed and uncompetitive economy. The poor will be hurt by both slow growth and lack of jobs. Conversely, low-income countries that open up and maximize their comparative advantage tend to enhance their growth prospects and raise their income potential, which are keys to job creation and poverty reduction.

Although the newly released poverty numbers may make the work of policymakers and development experts more humbling, the numbers also present an opportunity to reassess what has been learned so far. Increasing openness as a way of tapping comparative advantage will enhance a country's growth performance and help reduce poverty. In the end, the inconvenient truth—that there are many more poor people in the world than previously thought—could actually improve our understanding of the development process and our efforts to reduce poverty.

References:

Chen, Shaohua, and Martin Ravallion, 2008, "The Developing World Is Poorer than We Thought, but No Less Successful in the Fight Against Poverty," Policy Research Working Paper 4703 (Washington: World Bank).

Lin, Justin Yifu, 2007, "Economic Development and Transition: Thought, Strategy, and Viability," Marshall Lectures (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press).

Porter, Michael, 1990, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (New York: The Free Press).

Ravallion, Martin, 2007, "Inequality Is Bad for the Poor," in Jenkins, Steven, and John Micklewright (eds.), Inequality and Poverty Re-examined (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Ravallion, Martin, Shaohua Chen, and Prem Sangraula, 2008, "Dollar a Day Revisited," Policy Research Working Paper 4620 (Washington: World Bank).

![]()

![]() The operator gets traffic on its network, the driver gets a commission and the consumers get access to affordable calling

The operator gets traffic on its network, the driver gets a commission and the consumers get access to affordable calling ![]()